If At First You Don't Succeed, Quit...

If at First You Don’t Succeed, Quit… (Director's cut from my TED speech - thanks to Monica for editing)

First race and overcoming:

When I was 10 years old, my father took me to a speedskating meet. My very first race was 3 laps long. I quickly got so far behind that by the time I finished my second lap I had been lapped by all 8 or 9 of the other boys and girls. I tried to stop and quit right there but the judges and parents wouldn’t let me, so I skated the final lap all alone, in tears, humiliated. I wanted to quit the whole sport right there but my father wouldn’t let me and that turned out to be a good thing. A year and dozens of practices and races later I squeaked by to a third place medal at the Michigan state championships.

This progress and success then became a stepping-stone to a career on the U.S. National Speedskating Team and eventual competition in 9 world championships. It all culminated in a silver medal at the winter Olympics held in Lillehammer, Norway. By the way, you will likely not remember that event (this was pre-Apolo Ohno) not just because it was an obscure event in an obscure sport buried on the last day of the Olympics. No, the reason you wouldn’t remember this performance, but that you WILL remember these Olympics is really the same thing, specifically Her (Tania Harding), Her (Nancy Kerrigan)… and of course, This (Hammer on Nancy’s knee) and… again.

Obvious questions, not-so-obvious answers:

So an obvious question people ask of Olympians is “what advice would you give others aiming to follow in your footsteps?” And the obvious answer includes well trodden advice like, “Do your best, work hard, keep your head down, never give up, never give in, never quit, when the going gets tough, the tough get going.” These words are exactly what my 10 year old self needed to hear and they were - and are - true.

Parents, teachers, and coaches around the world repeat these words over and over and for good reason: kids have a remarkable capacity to quit something well before they’ve had the chance to determine if they are any good at it. So we use these words, along with stricter measures, to ensure that they acquire the discipline, the ability to delay gratification, and the tenacity to stick things through, when things get hard.

The Stanford Marshmallow experiment, conducted in 1972 is perhaps the most famous and successful behavioral experiment corroborating this foundational approach: children who were able to delay eating a marshmallow in order to earn two marshmallows a few minutes later were shown repeatedly in a longitudinal study to have greater success in life – higher SAT’s, greater incomes.

It works. I suspect most of you here in the room who can ante up $50 and miss work on a Friday to listen to new ideas about positive change have mastered the capacity to delay gratification and struggle through a tough present for the promise of a more rewarding future.

Yet… Yet, for you successful adults in the room, I think this guidance has gained unintentional momentum and these same words have subsequently become a pack of lies, a collective adult neurosis unintentionally designed to rob you of success and happiness.

Yes, I said it, “a collective adult neurosis.”

“Wait,” you might say, “How can that be?”

I have witnessed over and over that as we master this ability to “tough it out”, the obstacles we overcome grow ever larger, the delayed gratification we pursue gets farther out and all this grows without bounds, and at some point a mindset and momentum take over such that overcoming obstacles becomes the defining drive, and delayed gratification is delayed indefinitely.

The risk is that we transition, subtly, to a life focused solely on overcoming the insurmountable: weaknesses. Hearkening back to our marshmallow experiment, it appears that some of us have traded not one marshmallow for two but an infinite number of future marshmallows for an infinite future date.

When discipline completely replaces inspiration, a kind of desperation sets in – a “quiet” sort as famously described by Thoreau. It is not exactly failure, but what is it then?

“Most men live lives of quiet desperation” - Thoreau

Perhaps you still have your doubts. Here, let me prove it to you in two different ways. This is the audience participation part of the program – I’ll need you to finish the following two phrases – be nice and loud so the microphones can hear you.

"If at first you don’t succeed…" (try, try, try again.) Great – everyone knows that one. How about this one?

"The definition of insanity is repeating the same thing over and over again, and…" (expecting different results.)

OK, perhaps that is too clever, too trite. But really, when does “try try again” become insanity?

Here is another way to think about it. One that, perhaps, may hit closer to home. Have you ever pursued something, an activity, a sport, music, a class, a project, a job or a career, and after it was all over said to yourself, “wow, that sucked.” And the kicker: “I didn’t even realize it at the time.” If you nodded or smiled or identified with this description, you may be at risk of a weakness focused life of quiet desperation.

Let me give you a new refrain: Once you have established that you are able to defer gratification, a new rule of thumb perhaps should be, "If, at first you don’t succeed, QUIT.

That is “QUIT and do something else." I can just see the slogans for this movement, “Quitting is cool! Quitting is good!” We could make T-shirts, “I Love Quitting.”

Actually that’s not quite right – tenacity and resilience are key to success throughout life. But they need to be tempered by the ability to avoid the trap of banging your head against the wall in an endless and desperate pursuit of weakness.

What if quitting isn’t right but head banging is getting you nowhere? You need a different plan. I have one, this plan is based on , guidance taught to me years ago by my coach Mike Walden whose advice helped change my life. “If at first you don't succeed, find a way to "1) Race your strengths and 2) Design around your weaknesses."

Let me illustrate.

Assessment 1: When I was 21 I graduated from Stanford University where I trained on borrowed ice with no coach and no team but nonetheless managed to come in 12th place at the world short track speedskating championships in the 500m that year. After graduation, I joined the national team full time and moved to Colorado Springs to train at the U.S. Olympic Training Center with the likes of Dan Jansen and Bonnie Blair for the first time. As a part of the program in the first few days of the training camp they held a series of assessments – the “SAT and ACT” of aerobic sport.

The morning of that first performance assessment I walked across the campus of the U.S. Olympic Training Center and entered the confines of a former army barracks now retrofitted for its new purpose. I was surprised to find shiny white tile floors, white walls, white fluorescent lights and the acoustic tile ceilings reminiscent of a hospital. In the testing room at the end of the hall there was a half dozen people in the room in medical garb and white coats, a stationary bike, and a cluster of equipment surrounding it. I was suddenly uneasy, noticing streaks of what appeared to be blood on the floor under the bike.

I climbed onto the contraption and all at once the room became a hive of activity: extended fingers pushing buttons, cords clicking into machines, and the shiny steel mandibles of various instruments gathering my vital signs. One attendant began to slather a clear cold gel on my chest while another began sticking a dozen circular black rubber suction cups into the viscous goo. A third attached electrodes to the rubber sensors, while a fourth pried a finger loose from the handlebars and, without asking, stabbed the meat of my fingertip with an ordinary pin she had just swabbed with alcohol, greedily milking the blood out of it into a tiny glass test tube and then disappearing into the hallway behind the machines without ever so much as a “please” or “thank you.” Like a fly in a spider’s web, I was turned, prodded, and poked.

The web of wires from the machines around the room were then clipped to the electrodes on my chest and back as though I were ready to be lit up like a wedding gazebo. Finally the doctor approached, consulting his shiny metallic wristwatch and asked, “are you ready?” But he wasn't talking to me.

His assistant approached saying, “this may feel a bit awkward” as she fitted an ugly contraption from an orthodontic patient’s nightmare onto my head – crisscrossing straps pressed into place over the top of my scalp supporting a mechanism that that contained a short length of a thick plastic tubing.

I didn’t mind it so much until they rotated the large tube into place in front of my lips and then said “open” and then jammed it backward into my mouth. My jaws were ratcheted open like a dental X-ray and then left that way. Another intern brought over what looked exactly like a long hose from a vacuum cleaner and attached it to the other end of the tube in my mouth. The far end of the 15 foot tube dropped to the floor and then rose again to where it was connected to one of the many large machines in the room.

Even as my jaw began to ache from being pried so wide, the doctor said again, “ready?” but he still wasn’t talking to me. It was to another white coat who snuck up behind me and placed an ordinary wooden clothespin over my nostrils to keep me from breathing through my nose. My claustrophobia reached its max and I had to fight the gag reflex. It got worse when I considered that others had had this tube in their mouth, and others had had the gag reflex…

Fortunately I was distracted by the start of the test and all the assistants and lab coats disappeared into far corners except for one of the younger interns in the room who advised me in monotone, “Just maintain 90 rpms – we have set the resistance at 175 watts and every two minutes, we’ll increase the resistance and rpms until you reach your max.”

Translation: pedal until you die. I was on an escalator to hell.

At two minutes the intern was back, turning the dial of resistance and informing me, “You are now at 200 watts of resistance – please increase your rpms to 95.” At the same moment the vampire with the pin suddenly stabbed a second finger and began sinuously squeezing that finger to extract more blood. I would have said something except for the tree trunk in my mouth.

For the next 6 minutes I pedaled and entered that middle realm of work on the bike that is satisfying and then hard. I monitored my rpms and my heart-rate and watched it climb from the 140’s to the 160’s into the 180’s. I began to sweat a lot which didn’t bother me. I began to drool a lot, and that bothered me immensely. I watched the spit as it stairstepped down the accordion layers of the tube and then followed the hose back to the machine, then the machine to the heavy black cord, and the heavy black cord to the outlet in the wall. I began to consider the physics of electricity – voltage and amperage – and the conductive properties of water. This was all rational cover for my building claustrophobia. I pedaled and tried not to panic.

Each 2 minute interval brought the return of the intern and the little vampire as one would announce the new level of torture and the other would stab a new finger. After 8 minutes of this I was suffering intensely and convinced I was almost done.

“Halfway” said the white coated intern smooth but emotionless, “shoot for 16 minutes.” 16 minutes?! NO F’ing’ WAY! I thought as she changed the resistance to 275 watts and asked me to increase my rpms to 110. I decided to shoot for finishing this 2 minute interval.

It got hard – really hard. My lungs worked like bellows, and my thighs began that burn from lack of oxygen. Head down I had lost all contact with the tube and the vampire and the lab coats except for a sudden realization that they were all drifting back into the place. My suffering was a magnet pulling them in, and the harder I worked, and the more my heart rate climbed, the closer they got, and the more they talked to me. I wondered, what kind of people are attracted to suffering like this?

My pulse entered the 190’s and then the low 200’s. I was pulverizing the pedals and the air in my lungs began to burn. Somewhere around this time, the vampire began slashing my fingers at 30 second intervals and I stopped caring which finger had holes in it already. Sweat coursed off my body, and rivers of saliva drained into the tube and I finished off the 10 minutes and it was time, again for an increase.

This time it was the doctor himself: “300 watts, 115 rpms – from here on, the rpms will stay the same. Please continue” and I felt the resistance increase yet again. The resistance was less of a factor than the increase in rpms. 115 rpms felt like a hurricane for my tired legs and I was certain I would last less then 60 seconds.

The group that had gathered sensed this internal negotiating and one said, “make it 60 more seconds – you can definitely make that.” I looked up and noticed my heart-rate – 210 beats per minute. I determined to make it the full 60 seconds and did – but they were ready, “Make it 60 more seconds! You can do it!” They pressed closer, unrelenting. I made twelve minutes – barely.

I tried to quit, but there were 5 faces in front of me and none were relenting. By now my legs were gigantic burning red balloons and my lungs were embers. Still I struggled on and when my rpms dropped below 115 they poked and prodded and I returned to 115 on the monitor. At the new resistance of 325 watts I aimed for 30 more seconds and made it. Then 30 more and I made that. The vampire continued to collect her blood from my bloody fingertips without the pin as we’d given up trying to close up the holes in between. The floor had series of bloody drops diluted with sweat.

I slowed at 13 minutes, pulse at 215 but they were ready, screaming “go, go, go! 10 more seconds” as my pulse climbed to 215. I made it and still they pushed “10 more!” Knees flailing, lungs flapping like bellows I continued and the wheezing and rasping sounds of my death rattle began. At 13:15 my body began to implode. My heart rate had reached 217 beats per minute. I tried to follow directions from the room to make thirteen and a half, but a few seconds later my legs, my lungs and and my heart gave in and the clock stopped at 13:26.

They all congratulated me in a seemingly sincere way, so I assumed I had done well, and that 16:00 was the “holy grail” and that I had gotten close. The vampire excitedly mentioned that I had one of the highest lactic acid levels they had measured as well. I said “that’s great!.” “Wait what does that mean?” Her answer in a matter-of-fact tone, "You are good at suffering."

Great.

I could barely crawl down from the bike after they removed the tube and all the wires, and with considerable effort grabbed my shirt and walked back down the hallway to the dressing room. I was gray.

I dressed and headed back to the dorms. After a convivial dinner with my roommates and other skaters I received a manila envelope under the door with my test results. I tore it open eagerly, excited to see my results. I had been congratulated. The interns, doctor, and vampire had been genuinely interested. I had worked harder than most humans are capable of conceiving and suffered to the point where I nearly passed out. I had been 12th in the world the prior year at age 21 with minimal training. I expected results that matched my talent, my effort and my prior performance.

I failed to mention something that had happened right after finishing my test. As I left the testing room and hallway, along the way I passed the fresh faced cyclist I vaguely knew by the name of Lance Armstrong on the way to his V02 max test. 19 years old and on his first trip to the OTC he nonetheless offered me some EPO and steroids, which I refused.

As it turns out I should have taken them because these are the results shared with me from the test:

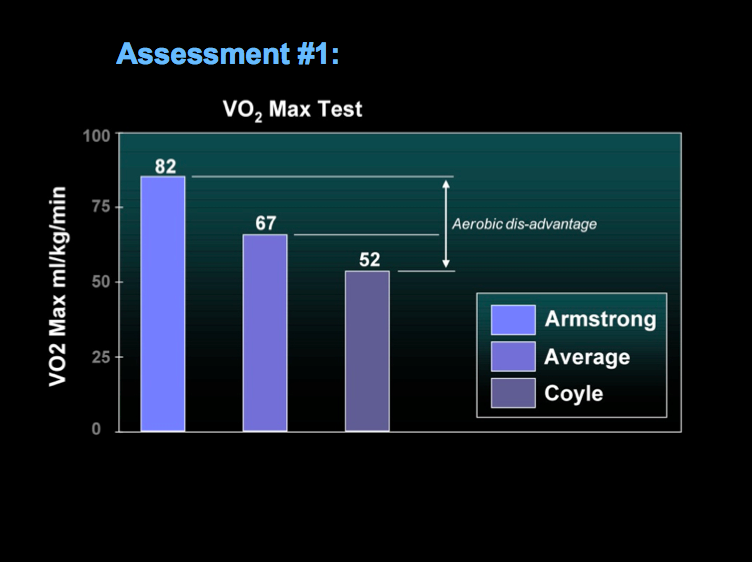

According to this test, I had the worst VO2 of the entire team – and this was a test the coaches had suggested was the single greatest predictor of success in our sport. Later, I learned that Lance Armstrong had survived 26 1/2 minutes and maxed out at 500 watts. When I was done ready to fall on the floor, he was only halfway – and it only got harder.

The coaches made no bones about what this meant – that I would have to work harder than anyone to overcome my weaknesses – that I would have to do more aerobic work, more endurance work, more volume to overcome my weaknesses. They were in my corner and wanted the best for me so I believed them.

First Point: This brings up my first point – in order to design around your weaknesses, you have to know what they are – and accept them. This was an obvious and real data point and if I had been able to be objective I could have used it for what it represented: a revealing portrait of the nature of my weaknesses. As it turns out I have never been good and will never be good at putting out a steady output at a high level for long periods. But, what I read out of the graphs and data was simply, “I suck, I suck, I suck.” At age 21, I wasn’t ready to use negative feedback to my advantage. I repudiated the test, the doctors and the coaches. This despite the fact that I ended up doing this test 2 more times over the coming years and scored – you guessed it, exactly a 52.

Fortunately, there was a second test to complement the SAT of athletics – the ACT in this case was a test called Max Power Output or Wingate test which sounded right up my alley as a sprinter.

A few days after the VO2 test, we received time slot assignments, and like before, I showed up to another low-lying barracks. Like before there was a hallway to a small room with a stationary bike. Unlike before, the hallway was carpeted as was the room, and there were no big machines and only a few attendants, and no white lab coats. It was comforting at first until my nostrils recoiled at a scent vaguely remembered from grade school – the unmistakable stench of vomit hidden under sanitary cleanser. Once again I got nervous – now what was it I was facing?

An attendant asked me to get the seat height set and make sure everything was comfortable. There was no eye contact. I did so. He then explained the nature of the test, “30 seconds with resistance, all out – as fast as you can go, we’ll measure your average and peak output, got it?” I nodded. “Remember – hit it full out from ‘go’ else the test is wasted,” he added.

I said “got it,” and got my feet cinched in good even as the other technician began to turn the dial on the front of the flywheel while holding his clipboard.

“All set,” he said, and then the first attendant said, “you might want to test the resistance…we set it at 710 watts” Until this point I still had confidence. 30 seconds on a stationary bike with a flywheel to send zinging – how hard could that be? Finally, something I’d be good at – a way to race my strengths instead of wallowing in my weaknesses.

A half second later a rush of terror hit, bringing a flush of sweat to my body despite the dry air. When I pressed on the pedals, all that happened was that I stood up. I tried again – with my right leg in the two o’clock position I put my weight into the pedal and all that happened was that my body lifted from the seat.

“Um, I think the bike locked up,” I said, hoping to disguise my panic.

“No no,” the two assured me in unison, and then one continued “just push real hard, you may have to pull with the other leg – you’re no lightweight, so you’ve got 710 watts of resistance on due to the ratio with your weight so it’s a bit hard to get started.”

In disbelief I used all my might to push my right leg down while straining with my left hamstring to raise that leg. My right foot moved down six inches but then immediately stopped from the immense friction. Suddenly the concept of 30 seconds became an eternity – to pedal THAT for a half minute! NO WAY!

But they knew better than to let me think it over, “3, 2, 1, Go! GO! GO! ” And I drove my right quad with all my might and convulsed my left hamstring to lift at the same time. Sure enough, the shiny chrome 50 lb flywheel began to turn, sluggishly at first, then building. 1, then 2 seconds passed by and I began to get the rotational energy going. I moved out of the panic zone and began to really pedal and the two assistants continued, like me, to watch the seconds tick, and the RPM’s rise on the monitor.

Two and a half seconds in and I was entering a realm on the bike that has always brought me joy – that of energy crackling out of my legs - as, 3, 4, 5, 6, seconds passed and my feet began to turn circles, spinning, then buzzing with a kind of manic yet fluid energy despite the heavy resistance. The shiny flywheel began to fly and I could feel the heat rising off it and smell it in the air.

I distinctly remember looking around the room at the astonished faces of the attendants as my feet hummed along and my rpms rocketed up 100, 180, 200, 220, 240 rpms, the bike vibrating the air and the floor as though I might lift off. Now, at 7, 8 and 9 seconds, for once the faces were interested in something other than my failure. For the next two seconds, as heat continued to rise off the flywheel, I played roulette with my body having no idea what was to happen next.

How does that verse go? “Pride goeth before a ..?”

“Fall.”

9, seconds then 10... and my began feet slowing, subtly at first, but then dramatically as the humming energy faded to hollow emptiness, 11, 12, 13 seconds, laboring, and the massive anaerobic effort suddenly rolled into my lungs and legs and brain all at the same time like a thunderstorm and a wave of paranoid fear rolled over me as the walls and ceiling of a tunnel of pain closed over my head.

I continued thrashing forward under the dark nape of terror, but all air was gone and the horizon continued to close as my lungs caught fire and my legs become molten lead.

Running out of air creates fear in one of its most raw, painful, debilitating forms – a deep inner panic that starts to simmer and boil over – to pervade everything – telling you to find a way to surface, to escape this intentional burning drowning. But there was no way out and like the VO2 test, the attendants were ready and had moved into a small semi-circle in front of the bars, “Keep it going! 14 seconds! … Halfway!” My legs had gone from 200 rpms down to 100rpms in 2 seconds. I was dying and there was no blood left in my whole body: it had been replaced by battery acid and fire erupted in every synapse and I had a mouthful of pennies. “16 seconds! 100% effort! You are on a good one!” they cried and suddenly their faces zoomed in and grew whiter even as an odd buzzing began.

Sixteen, seventeen, eighteen seconds and the dark tunnel I was in suddenly began to open and brighten and I began to hear a new sound: a buzzing and throbbing like cicadas and a gong inside my head.

My laboring legs dropped to 50rpms, then 30 rpms. I had never felt pain this excruciating. “Nineteen, twenty, twenty-one seconds!” they screamed, the attendants were leaning in now, faces only inches from mine, shouting – yet sort of in slow motion, with fading sound – just movements and mouthing words and this ever-building buzzing and brightening. I was strangely interested in how overexposed everything had become. I felt my legs stop and looked upward as the crescendo arrived – a convulsive rotation up and over my head like a low flying helicopter. Everything turned white then yellow then black as I dropped into the mesh of nausea. Then it was quiet.

------------------

When I woke up, I was on a cot, in another room. My little vampire, disguised in plain clothes was stabbing my finger excitedly as I opened my eyes, “you are OK – great lactic acid readings!” Another voice, one of the attendants, was irritating me, talking loudly on the phone from another part of the room, in response to some ongoing dialog, “…yeah I know! (laugh) But no one has ever passed out ON the bike before!”

I was disgusted. I got up, woozy, and hands steadied me. Voices seemed to be indicating success like the last time after the V02 but I wasn’t buying it and couldn’t wait to get away. They continued their monologue with something about peak power and rapid decline but I thought to myself with contempt, “here’s the real test – the one I thought I’d finally get some results worth having.” “Instead, I barely finished half the test without passing out.” “I suck, I suck, I suck, I suck…” Over and over those were the words my footsteps repeated as I strode back to the dorms.

When the manila envelopes were passed out that evening again under the door, I didn’t bother to open mine for a while. Finally, when no one else was around, I lifted the flap to my reality – it looked like this:

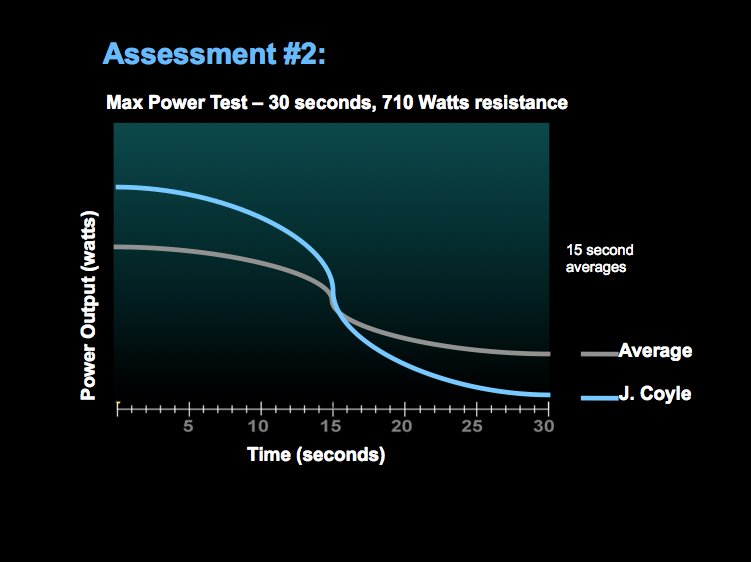

Once again I had the lowest average output of the team, however in the different slices of time, the charts became potentially interesting: at my peak, I had produced 10.9 watts/kilo and a peak power 1785 watts – the highest of the team regardless of weight. The data showed that I have a little secret nuclear power for 2 – 5 seconds under heavy resistance.

This is just fantastic news in a sport where the shortest event is about 45 seconds. Unfortunately, as the doctor who reviewed my chart with me noted, “you also have the highest rate of decline of anyone on the team.” Thanks doc, for pointing out the obvious.

Here was the clincher for me: how is it possible I could ever hope to be good at this sport? Yet, as I reminded myself, I already had been. I had been quite good – even at events lasting 2, 3, even 7 minutes… In hindsight there was something significant here that I only figured out many years later.

Second Point: This brings me to my second point – in order to race your strengths, you have to know what they are – and not in the general sense like “I’m fast” or even in a category sense of “I’m quick for short distances – I’m a sprinter.” No, strengths are often extraordinarily specific to capabilities released in a specific environment under just the right conditions. I believe the true nature of identifying a strength takes context and repeatability into its definition until one’s true talents are very specifically identified.

What I could have learned about my strengths that summer took me years to figure out – because there was no test for my strengths. As it turns out my superpower is not only that I can generate a high level of output under resistance for short period of time, I can also do it repeatedly with a short rest, which just so happens to perfectly describe the sport of short track speedskating – spikes of power under heavy load in the corners for a few seconds followed by a relatively light effort on the straightaways for “rest.”

At that time, however, the coaches got through to me and showed me “the light” – to find success I should be reasonable, adapt myself to the program and train my weaknesses. If the tests were right, I either had very little talent – OR I had significant weaknesses/opportunities that needed to be shored up. This was the best half-full I could make of it: that I had weaknesses to be trained. I left the camp with a mission to out-train my weaknesses and show the coaches, athletes, and the world what I was capable of. It was the only reasonable solution. And, by the way, it looked, and felt just like this:

For the next 4 years I followed the national team program and focused on ‘fixing my weaknesses.’ And the results? Before the test, while a senior at Stanford, I was 12th in the world while training on my own. A year later, training full time under the national team program, I didn’t even make the top 10 in the country. A year later in 1992, an Olympic year, the team wasn’t even a dream and I finished further back in the U.S. nationals than I had since I when was 13 years old, ten years prior.

Perhaps I should have quit. Occasionally, though I would have days where everything clicked and I was capable of things no one expected, not even me. Those days kept me going. That, and I had begun to rebel against the constant focus on my weaknesses. I became “unreasonable” as I was often reminded. My new coach again perpetuated the belief that I would need to fix my weaknesses by working harder and designed a program to do so with extra focus on endurance and workload. But I had lost faith in coaches and programs and began managing it by rebelling. When he would say, “John go ride 100 miles” on the bike when the rest of the team would be doing jumps or some other activity, there were a few occasions where I was caught coasting back into the Olympic Training Center parking lot 45 minutes later. “100 miles in less than an hour – you must have really been flying” he would say.

"A reasonable man adapts himself to his environment. An unreasonable man persists in attempting to adapt his environment to suit himself. Therefore, all progress depends on the unreasonable man."

George Bernard Shaw

Still, by protecting myself from the destructive force of an intense focus on weaknesses and overtraining I made the team again in 1993 and earned a top 3 spot on the Olympic team in 1994 where we ended up winning a silver medal in the relay. But that is not the interesting part. The interesting part of this story came in 1995.

After the Olympics in 1994 I considered retiring – quitting. I had achieved a lot of what I had wanted to achieve in the sport and considered it might be time to actually stay in one place and earn some money. The beauty of being willing to quit something is that it gives you perspective. And sometimes, perspective allows you to see things that perhaps should have been obvious – in this case it looked just like this:

Third Point: This brings up my third point – it is essential, occasionally, to get perspective. Sometimes the impenetrable walls we are facing have edges. Sometimes all we have to do is get perspective and walk around them. In my case being willing to quit allowed for a departure from the weakness-focused approach that had consumed my life for the last four years. I decided that if I were to keep going , I would do it differently, that I would focus more on my strengths, and what I did best, and the things I wanted to do.

So… I quit: the national team, not the sport. I moved to Milwaukee with a couple other skaters and we trained on our own in a self-designed program. I started doing more jumps, sprints, heavy squats – things I liked, things I was good at, things that leveraged my strengths. I also still did the aerobic and endurance work – just not every day and not back-to-back.

I also looked at the way we skated, not just how we trained.

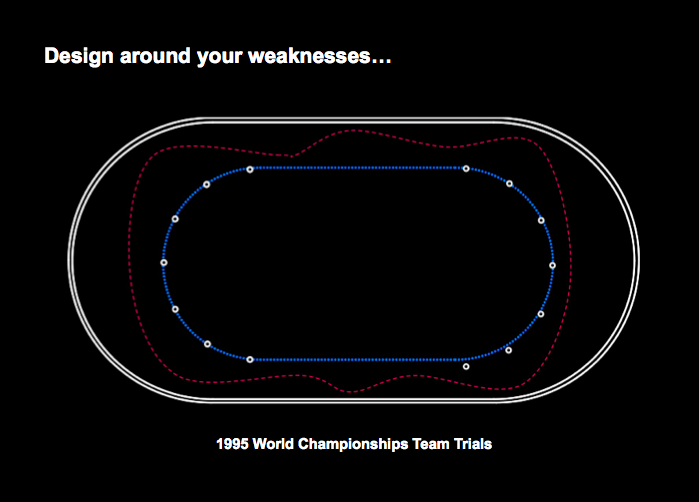

As you can see from the diagram, we skated our track much like NASCAR drivers race – swinging wide before the corners, narrowing in at the center of the corner and then swinging wide coming out. There was a good reason for this, let me explain: flinging around a hockey rink at 35mph on brittle ice is a pretty scary thing. Skaters had developed this wall-to-wall approach in order to even out the level of effort around the 110m track and minimize the intensity of the g-forces in the corner, reducing the risk of a crash. In doing so we also added about 10 – 12 meters or 10% additional distance per lap. I decided to change my approach and to try and skate only 110 meters. I figured that if I couldn’t skate as far as fast, I would just skate less distance.

I also determined that this approach, which would feature more of an intense pulse in the corner and a bit of a rest on the straightaways, might better suit my strengths.

I practiced this tighter approach all through the early season skating tight to the blocks and putting my energy directly into the apex of the corner: at top speed this meant 2G’s of compression and translates to completing a one legged 350 lb squat from a deeper-than-90-degree knee bend leaning sideways at 60 degrees all while balanced on a 1mm wide 18 inch long blade traveling directly at a wall at 35mph. I got good at it.

That fall I started the MBA program at Kellogg and decided to skip the world cups in order to not miss classes. I also started part time work as a product design engineer. As January rolled around, I limited my work schedule and cut back to one class at Kellogg and prepared for the most important domestic meet of the year, the U.S. World Team trials to be held in Saratoga, NY. I did not have a lot of competition under my belt and was worried about my level of training and fitness.

I flew to Saratoga about a week before the trials to prepare. However, the day after I arrived, I came down with the flu. Not the stomach flu or gastroenteritis, the real flu. For the next 4 days I never left my tiny lofted bedroom in my host family’s house and I stopped eating anything but saltine crackers. When I finally showed up for practice the day before competition, I was down about 10 lbs and weak beyond belief – a few laps on the ice and I had to throw up and then quit. Back to bed.

The next day was Friday, the first day of the trials and the first of 11 consecutive races required to select the team. It was the qualifying round and consisted of a 1000 meter time trial to narrow the large field of skaters for the subsequent rounds to a manageable to 16. The 1000m time trial is run pursuit style: two skaters at a time on opposite sides of the rink chasing each other for 9 laps of 110 meters.

A year earlier, in Lake Placid during the 1994 Olympic trials, I had finished 4th in this same event with a time of 1:32.90 seconds. I knew I probably needed to skate a 1:36 or so to qualify in the top 16, but my state of being was such that I had little hope to achieve even this qualifying time.

I decided to focus on the only thing I could control – the tightness of my track. If couldn’t go fast, I’d go short. So I went back to the locker room, and went through all the motions of preparation but with none of the usual mental gymnastics. I was numb. I would focus on one thing and one thing only: my strength -- skating tight.

I put on my skates, and then walked out onto the ice and removed my guards. We lined up across the rink from each other. I have a very distinct memory of complete and overwhelming weakness and misery just before they shot the gun. I thought there wasn’t a chance in hell I was going to finish the thing, but at least I had showed up. I figured I might as well put in a couple decent laps before the next round of being sick.

After the starting gun I went through the motions: skating a tight track right from the get-go, heading right at the first block and staying within inches of each of the markers around the corner. I held back quite a bit and moved into a zone of complete focus on technique, body position, and most of all, just staying tight to the blocks.

The first few laps went fairly easily, as expected, considering I wasn’t really racing all that hard. But despite my churning stomach, and lightheadedness, I started to feel a distinct sense of control, mastery of what I was doing, something Csikszentmihalyi would describe as “flow.”

Three laps in and suddenly something, or rather someone, broke my concentration. Suddenly my pair skater was in my sights on the straightway. Unbidden the sudden thought of, “Man, he must really be out of shape” came into my mind: afterall, I was nearly on my deathbed and it was becoming pretty clear that I was going to catch him.

Focus resumed, and I noticed how my blades were following the exact same line on the clean ice from prior laps and consciously drifted about a centimeter right in order to create a new “lane” for my blades. I wasn’t all that tired yet.

5 laps in and I noticed a strange change in the atmosphere. Normally the rink is quite loud with a buzz of conversations, shouts, and chatter, and it seemed to have all gone quiet except for the quiet announcement of lap times. As it does sometimes, my awareness expanded to understand the change in climate. The lights grew brighter, the ice grew darker, and the lap times made no sense. “9.1” someone said and whispers repeated it. What does that mean? That’s too fast – can’t be right – so I refocused and continued to pulse hard on the corners, tight to the blocks and drift easily down the straightaways recovering.

Meanwhile the officials were yelling “TRACK!” and my pair skater swung wide about 6 laps into the race. I slid past him with a head of steam still just focused on staying low, tight, and in control.

I could see faces pressed up against the glass now, lighting up in that way they do when they are seeing something special. It is a weird feeling to know when the audience is watching, but I knew and for the first time I allowed a bit of effort to escape into my tightly controlled laps.

The race continued and I kept my focus on laps 7 and then 8 while increasing my level of effort a bit to finish strong. I heard another lap time of 9.3 which didn’t make much sense, but I realized that I would at least finish.

The dinging of the bell broke me out of my reverie, just one lap to go. I had some juice left and I let it out a bit, but still kept my focus on staying tight. Right on the blocks I swung around the first corner as if on rails, a pair of straightaway strokes, and then one last hard crossover into the apex, 2 quick exit strokes and then across the line and it was though the whole arena sighed as I stood up.

It was quiet. There was whispering. I coasted and felt my weakness, doubt and worry resume. My inner monologue thought, “I suck." "It is quiet because they all know how poorly I just skated, I probably didn’t make the cut – no world championships this year for me." No outfitting with the huge duffel bag, the 2 skinsuits of new unseen design, the 2 sets of warmups, hats, gloves, sunglasses – no – all that would go to some rookie.”

I coasted around and, oddly, my coach had leapt over the wall and was on the ice and standing in my path with a weird, crazed look on his face, holding up his stopwatch as though I could read it from a distance. I nearly bowled him over and he hugged me to steady me and shouted “Coyle – what the hell you been doing in Milwaukee?”

My emotions surged in defensiveness, “I’ve been sick!”

“1:28 Coyle,” “You just skated a 1:28 - five seconds faster than your personal record.”

“You just skated 2 seconds faster than the American record.”

“Coyle, you just skated faster than the world record in a distance you hate!”

He held up the stopwatch and gave me one of those looks he had where he knows so much and you know nothing. I struggled to find any meaning. How could it be? I wasn’t even in my usual state of complete destruction… How could it have been such a fast time?

Why did I win against all odds in the 1995 U.S. Trials? Why did I fail so miserably in previous years under smart, well intentioned coaches? Years later and it all came into focus, thanks to the thesis in one of my favorite books “Now, Discover Your Strengths”, by Marcus Buckingham. Buckingham quickly summarizes the reasons why as follows:

“The definition of strength is quite specific: consistent near perfect performance in an activity.”

And,

“You will excel only by maximizing your strengths, never by fixing your weaknesses”

Finally, and potentially most important:

“You must derive some intrinsic satisfaction from it.”

This is the direct antidote to “quiet desperation,” and I was fortunate enough to have stumbled upon it.

I did not have much fun in the preceding four years up and through the 1994 Olympics. In the 1995 season I had an absolute blast, and I went on to set American records in 5 distances, won almost every 500m I competed in, and came home from the world championships with this piece of paper that I’m quite fond of, representing the fastest time skated in the world for 500m that year as well. Sadly this is a ranking by time rather than actual finish. In the semi finals I was tripped up from behind on the last corner and coasted across the line skates backward, missing making the final and a shot at the gold medal. Still it does give some pride knowing I skated the fastest 1000m and fastest 500m in the world that year.

Before I close, I’d like to share some practical advice on how to avoid a life of quiet desperation and to “race your strengths” in the more complex world of work and life. Sports are necessarily a simpler world than that of business but I believe that the same principles apply.

- Take tests & assessments. Find the bright spots (strengths). Toss the rest or design around obstacles (weaknesses).

- “You can't read the label from inside the jar.” Ask someone else for their candid opinion. Ask a lot of “somebody elses.” Anchor to the positive.

- Get exposure to a lot of things. Genetic predisposition + environment x interaction. Pay attention to your internal hum.

- Abide by the two year rule. If you’ve legitimately worked and practiced a certain skill for more than 2 years without results, it is probably time to change your environment, reframe, or … quit

- Quit doing the things you are not great at, unless out of love. If so make them a hobby so it doesn't matter. This sounds easy, but altering the trajectory of one's life is anything but easy.

To close, I’d like to revisit that quote from Thoreau. As I recently learned there is more to the quote than I originally knew and previously shared. Specifically, it goes like this:

“Most men live lives of quiet desperation, and go to the grave with the song still in them”

I have just one request of everyone here today. Please, please... Make sure that this is not you.

Thank you very much.