2014 Sochi Olympic Journal #10: How To Watch Short Track – Part 2

Tonight, the first set of short track races will be aired on NBC. The men’s 1500m Gold medal race is tonight as well as the women’s 500m heats and relay heats. Since it is tape delayed, here's a picture of us calling the races.  So, what can you expect tonight? Here’s a summary:

So, what can you expect tonight? Here’s a summary:

SHORT TRACK SPEEDSKATING – a primer

Basics:

The logistics of the sport of short track speedskating are easy to comprehend. A simple visual will suffice: inside the nicked and gauged plastic walls surrounding hockey rinks the world over an oval track is laid out using black plastic lane markers: 111.12 meters in length.

The short track rink

Add a half dozen speedskaters in their skin tight multi-colored suits racing for the finish line – like track and field or horse racing – and the simple format is complete.

The logistics of short track speedskating are also straightforward – a fixed number of laps (or half laps) comprising an even distance in meters (500, 1000, 1500, 3000 or 5000 meters), with the first skater across the line being first.

Time on the stopwatch, while an interesting anecdote, does not factor into the results except for the honor of holding a record.

Racing

Yet, like many things in life that seem straightforward, the actual play by play of the sport tends to defy the simplicity of its rules. Crashes, interference, and disqualifications factor into the results at levels unprecedented in any other sport, and even in “clean” races, the dynamics involved with multiple competitors lined up on a tight, short, narrow track of ice going 35 mph on 1mm wide, 17 1/2 inch blades means that the “fastest” skater quite often does not win.

One need only to remember watching the Australian Stephen Bradbury in the 2002 Olympics, who advanced by luck of disqualification in the 1000 meter heats to the semi finals. Self admittedly the slowest skater in those semi-finals, he proceeded to win that race – after all the other skaters crashed, placing him in the finals and into the medal round. Then again in the finals, while pacing off the back of a pack of top ranked USA, Korean, and Canadian skaters, Bradbury managed to avoid disaster and come across the line first – again not through his own merits – rather through the misfortune of the leading skaters. The gold medal was his – even though his efforts in all the preceding rounds suggested those of a non-contender.

Given the seeming randomness of the results, one might be inclined to shake ones head and put the whole thing down as a bit of a lottery. One thing is for sure, in any given race, luck will play a part. It is this unpredictability that makes it the crowd favorite for all the other athletes at the Olympics

Analogies

Short track tends to draw two analogies in sports – first, Nascar – due to the importance of drafting and the critical path skaters must follow to maximize their speed, and second, horseracing, for the relative importance of the track conditions and race length in the final result.

Who will win on any given day? It depends….

- Is the ice soft or hard?

- How long is the race?

- What combination of skaters are are racing? How will it play out?

- What unforeseen events will occur?

What does it feel like?

Think back to certain winter moments – those times of walking on slick, wet ice – to your car across frozen puddles, or down the sidewalk after a freezing rain.

Then remember that moment when your shoes first touched dry asphalt after sliding across the icy puddle, or the instant when you regained traction after passing back underneath the porch roof. To a speedskater, that is exactly what it feels like to be on ice with our long blades – it is feeling of traction and grip, stability and power.

An 17.5” speedskating blade on perfectly smooth ice is grippier than rubber on asphalt and more stable than a ski on snow. A Nascar can only pull 1 G-force on dry pavement, the space shuttle hits 3 G-Forces in launch, and a short track speedskater hits 2.7 G's at the apex of the corner.

The blade, its sharp edge, and its tracking ability while in motion, are able to smoothly receive every ounce of energy provided by powerful leg muscles to propel the skater forward.

Granted, the motion is sideways – like tacking in the wind with a sailboat – but the 17 inch blade is like yards of canvas gathering wind: the lateral forces are released in a tangential motion and converted to forward speed smoothly yet powerfully. Each stroke on the ice is a combination squat thrust (sheer power) and ballet (no wasted motion, fluid extension to the very tips of the range).

Now imagine that ultimate grip – no amount of effort will result in a slip – and a slow concentrated thrust through with the legs: massive force passing in liquid slow motion through the blade to the ice. The strength of the contracted leg is absolute, and the hold of the blade provides a supreme feeling of power. The controlled release of the piston-like skating stroke brings to mind the action of a hydraulic cylinder – a fluid, consistent, and powerful.

If you have ever had the ill-fortune to push a stalled car, and were lucky enough to have a curb or wall as a backstop for your feet, then that incredible slow thrust you were able to deliver to the car to get it moving is the closest thing in life to the feeling of a speedskating stroke: a 1000lb squat thrust.

Now, add to this motion the g-force dynamics and angles of a jet fighter and you have the right combination.

As a skater moves towards the corner, there is a momentary feeling of weightlessness as the body lifts with the final skate stroke, and then falls as the body and center of gravity compresses downward and sideways to enter the corner.

As the direction of the skater changes, centripetal forces cause a 2.7G acceleration to crush the body lower. In order to stay aligned over the center of the 1mm blades, the skater rolls inward, and the upper body leans way out over the blocks at an angle of 65 degrees+.

The powerful motion of the crossovers (corner strokes) then take over and compel the preservation of the momentum carried into the corner. Timed right, you’ll see the powerful transition of the full extension of the left leg underneath the right leg, both blades carving firmly just prior to the apex of the corner (the center-most block).

A smooth transition of the force between the two legs at that precarious moment preserves the integrity of the corner and allows the skater to enter a “pivot” – a one footed change of direction back toward the far end of the rink, and then relax the arc of the corner a bit through the latter half – reducing the G forces and allowing multiple crossover strokes of acceleration into the straightaway. The apex block is also the focal point of most crashes and many disqualifications. At the point of the turn the muscles of the body are stressed to the max – imagine squatting down to a 90 degree bend on one leg… holding it, and then putting on 2 of yourself on your back: the additional pressure provided by the almost 3G acceleration of the turn). Then balance all of that on a 1mm blade, headed toward the wall, on ICE.

As the skater exits the corner, the body decompresses and lifts with the center of gravity returning to vertical. A pair of straightway strokes later, and it starts again.

Is it hard?

This extremely controlled and concise motion is difficult. However – the motions are repetitive – unlike ballet the number of required motions is drastically reduced. The real difficulty of the sport lies in the compression of the body required to form the aerodynamic shape. Wind resistance, ultimately, is the primary obstacle to speed.

If speedskating races were held a vacuum, a skater could stand nearly upright and kick out a series of highly powerful shallow strides in rapid sequence to attain maximum speed. However, with the friction of wind the comes with speeds approaching 30 mph, the skater is required to try and form a teardrop shape, with arms and legs bent in a greater than 90 degree angle. The loss of muscular leverage at these compressed angles is severe – I won’t try to describe the physics, but just imagine these two examples:

1) Imagine if you had someone sitting on your shoulders. Now, in a fully upright standing position, imagine bending your knees slightly and then straightening them again. If you can imagine that situation, you probably can imagine that performing that minor knee bend and subsequent straightening would be very easy. The human body’s power output from near-full extension of the muscles involved is tremendous. Most of us could imagine even jumping a little with that weight on our back. However, this position is ineffective due to the constraints of wind resistance. Instead…

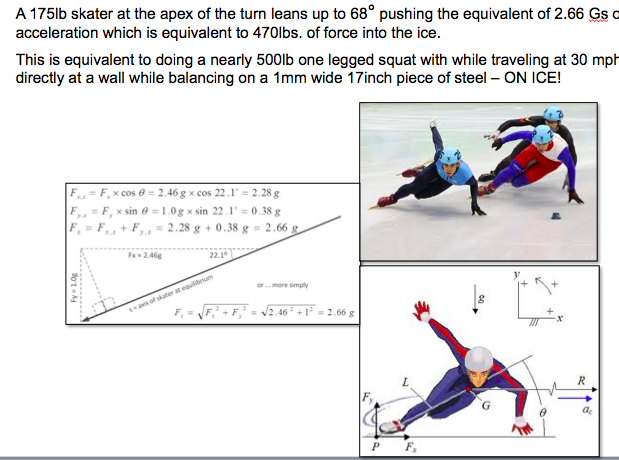

2) Imagine squatting down – all the way down, sitting on your heels. Then extend one leg straight out – kind of a Russian dancer stance. Now, balanced on that one foot try to stand up using only the completely bent leg’s power: nearly impossible for anyone other than an acrobat, Russian dancer, or speedskater. Do that with the weight of another person resting on your shoulders (from the centrifugal force) while traveling 30mph, tilting sideways at a crazy angle balanced on a 1m blade and you have the essence of the sport. (Here’s a rough diagram I put together for NBC with estimates of the forces:)

The compressed body position required by the aerodynamics of the sport demands high power from the legs in a full range of motion, with an extreme amount of coordination of balance, timing, alignment of weight and effort, and subtle coordination of a series of heretofore unused muscles in the abdomen, hip, knee, and ankle to ensure that the powerful compressed stroke passes evenly sideways without interruption or slippage.

This is why few that have started the sport after age 13 succeed, and how a 25 year old skater with 5 years of experience will look like an awkward novice compared to a 10 year old with the same experience. After some point, the synapses required for this kind of exquisite control wither away and cannot be trained.

The only exception to this hard and fast rule is the relatively recent crossover of in-line speedskating athletes. Not surprising considering the similarities of the two sports.

Why all the disqualifications?

In the relatively recent years since short track speedskating has entered the mainstream consciousness, it has brought along with it the expected perceptions of speed and danger and unpredictability. In addition, there also exists an ongoing element of controversy with regards to the judging system and the calls for disqualification (or lack thereof) that have occurred in many of Olympic races.

As an example we can remember back to 2002, where in the1500m mens final, a disqualification of Korean skater Kim Dong Song led to a gold medal – a first for American men – being awarded to Apolo Ohno who crossed the line second. However, the controversial nature of the call, and the dearth of medals for the strong team of Korean men led to highly publicized death threats from the Korean public. When Apolo returned to Korea for the first time since the 2002 Olympics for the 2005 world championships, he was met at the airport by 100 policemen in full riot regalia – just in case.

Then, of course there was the 1000 meter incident with Bradbury…

One unexpected outcome of all the uncertainty in the sport of short track is cultural in nature. One might expect that with all of the clashes and crashes, disqualifications and controversy that the tensions between rival teams and competitors might be very high: that the close proximity in the races might result in a natural distancing factor between athletes off ice and outside the venue.

Surprisingly, this couldn’t be further from the truth. A look at the sister sport of long track speedskating, a sport with no physical contact, few to no disqualifications, and racers competing almost clinically against the clock (in separate lanes and only two at a time) finds a culture where competitive tensions are at their highest. Long Track speedskaters are, more often than not, solitary, taciturn creatures, with serious countenances betraying the competitive tension embodied in every activity.

Short track skaters, in contrast tend to convivial, open and playful, with the occasional prank between and within teams a long standing tradition – a culture where each emotional explosion at the referees for a disqualifaction (or lack thereof) is equally matched by the off ice hijinks, stories and accompanying laughter between the skaters in their locker rooms, in the shared spaces playing hackysack, and back at the hotel over dinner. It as if the vagaries of the sport, the unpredictability of the results, and the shared suffering of uncertainty over the whims of lady luck has created a common culture of tolerance, humility and respect between athletes of different cultures, languages and perspectives.

There is an oft repeated, little understood phrase repeated consistently by the competitors that ultimately reflects this shared understanding. Apolo Ohno was interviewed on camera after the 2002 Olympic 1000 meter gold medal race where he crossed the line sprawled across the ice belly up in second place after being taken down from behind by a chain reaction four skater crash in the final corner. He had just lost certain gold to the unlikely Australian Steven Bradbury who glided in on the wings of lady luck – well out of contention – yet the winner of the coveted gold medal.

Asked for his views on the events that had unfolded, it would have been understandable if Apolo has been less than charitable: he could have said things such as “it was unfair, I had it in the bag, the Korean skater grabbed my leg, Steven wasn’t even a contender…” but true to the culture of the sport, and out of respect for the dozens, if not hundreds of races that Steven didn’t win under similar circumstances, Apolo merely shrugged, smiled, and uttered those those seemingly innocuous yet significant words repeated over and over in this turbulent and exciting world: “That’s Short Track.”

It sure is.