Design for Resiliency: Perform Better Under Greater Stress (and Like It)

(Reading time 7 - 10 minutes)

Most people think of resiliency as the ability to "bounce back" after a difficult or stressful event. This is, however, like suggesting that the opposite of a negative is "neutral." No, the opposite of negative isn't neutral, it is positive, and, as Nicholas Taleb characterizes so aptly in his book, "Antifragile" the opposite of fragile is NOT just "strong". The opposite of fragile is what he calls "antifragile" or what I will call "resilient." Antifragility and resilience are the property that results from not just bouncing back from stress, but from becoming stronger in the process. The rest of this post is dedicated to how to become more resilient and to perform better and thrive under even greater stress.

---------------------

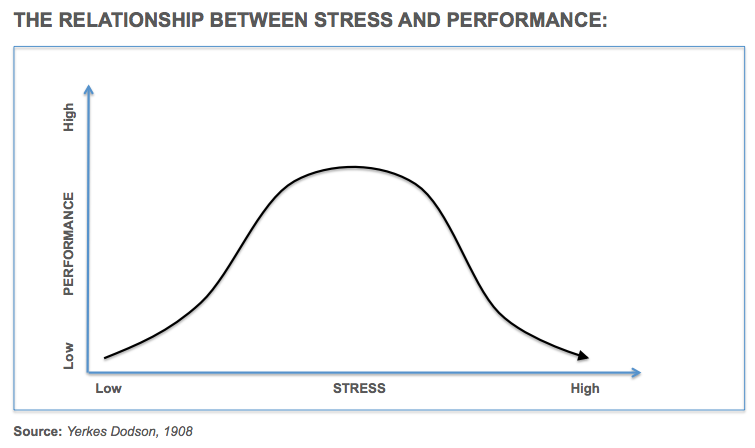

The Yerkes Dodson Curve: Stress and Performance.

In 1908, psychologists Robert Yerkes and John Dodson articulated the relationship between stress and performance: notably, that peak performance was not a by-product of low stress, rather that peak performance came at a certain "optimal" level of stress and then trailed off above that level.

This curve suggests and reinforces the idea that we must find balance - a concept now infused into the modern psyche. "Work-life balance," "finding balance," "reducing stress," and "managing stress" are now common buzz words throughout the working world. At first blush it makes intuitive and rational sense:

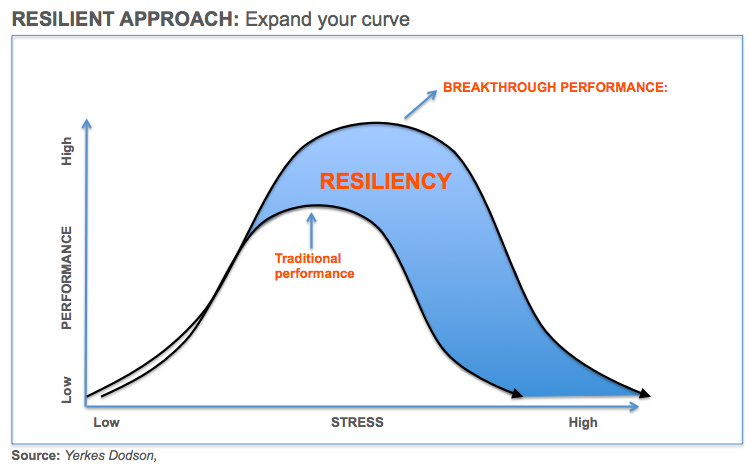

The philosophy of Art of Really Living, however, is different. We use a "design thinking" approach to challenge life's SOP's (Standard Operating Procedures). We believe that the central question of "how do I reduce stress to find balance?" is fundamentally the wrong question, because, it makes the flawed assumption that this curve is fixed. Based largely on the work of my friend and mentor Dr. Daniel Friedland we can understand that the curve is not fixed. Knowing this, we explore a better question, and one more apt for the modern world: "How can I perform better under even MORE stress?" Let's face it - this world is not getting less complex or slowing down.

"It will never be this slow again."

A daunting quote, but most certainly true. Accepting this, we can see that the better answer is to shift our stress response curve up and to the right - to perform better under even more stress.

When you think about it - this is EXACTLY what athletes have been doing for millenia: learning to shift their stress and performance curve up and to the right. In fact the curve looks an awful lot like a bicep. The stress in this metaphor is the strain on the bicep. The performance is the maximal weight the muscle is capable of carrying. So... how do athletes shift their curve and increase their performance / stress ratio? They intentionally take on more stress, and (and here's the key) then they recover. Episodic stress and recovery is the key to athletic performance. But here's where the modern "corporate athlete" often gets it wrong. In office spaces around the world, workers are doing the moral equivalent of 15 hours of dumbbell curls with no rest and little sleep and then wondering why their biceps are not growing.

The key to developing resiliency (and breakthrough performance) is the same: episodic stress, followed by recovery.

So, how to apply this new model of increased performance under stress to our busy lives? Here are 3 simple steps (that are not-so-simple to implement.)

1. REDUCE

2. RECOVER

3. RAISE

4. REFRAME

I'll cover each of these in brief:

1. REDUCE: Reduce current stress levels to allow for recovery. Many people I know are already to the far right on their stress / recovery curve and not in a position to intentionally take on more stress. So the first step is to reduce stress to allow for recovery - to regain initial balance. This is an intuitive step that many try in an episodic way, but it tends to form a vicious cycle of pulling back and out of things, recovering, recommitting, becoming overstressed and then pulling back again. A particularly terrible by-product of this cycle is being perceived as lacking integrity or as lacking follow through. Last minute cancellations, failure, over-promising and under-delivering are the hallmarks of this step by itself. Nonetheless it can be an essential first step in developing greater resiliency - here are 3 great ways to reduce stress:

a) "Race your strengths." Spend more time in your area of strengths - in "flow," "the zone," the peak performance state. Research shows that spending more time in this state significantly increases willpower.

b) "Design around your weaknesses." Stop doing things that you are not good at. Not good at making project plans? Make it a stretch assignment for a detail oriented go getter. Not a great driver? Join a carpool. Not great at your current job? Identify a better role and then lobby to move into it - or quit and find a more suitable job.

c) Delegate tasks that deplete you. Don't like doing taxes? Hire an accountant. Bored and overwhelmed by too many meetings? Quit the council, the PTA, the homeowners committee. Send a delegate to company meetings. Stop doing certain chores - hire someone to mow the lawn or clean the house. Money can't buy you love, but it can buy you time...

2. RECOVER: According to my friend Dr. Ari Levy, stress in modern life isn't necessarily up, but our ability to recover from it has drastically decreased. He makes a really good point: 100 years ago you could die at work from heavy machinery, or die on the way to work through exposure. Your children would often die at childbirth or later from the flu, typhoid, tuberculosis or even a snowstorm. If your crops didn't come in you could starve, if you ran out of firewood you froze. Fast forward 100 years and we are dying from... failure to answer an email quickly enough on our smartphones. But here's the thing... we actually are dying from email... We are bathing in cortisol - the stress hormone - 24 hours a day, 7 days a week which causes inflammation and wreaks all sorts of havoc, not the least of which is heart attacks, cancer and other killers. Dr. Ari had me play a guessing game to identify the top 3 ways to recover from stress. I guessed sleep, meditation and red wine. I was wrong on all three accounts. Here, from science are the actual top 3 in reverse order:

3) Low intensity exercise: I should have guessed this one. As an athlete, "rest days" were not spent in bed - no instead we went for a very easy bike ride, a very slow jog, or just went out on the ice without ever breaking a sweat. The Tour de France riders don't take their rest days off - they do "recovery rides" for 2 to 3 hours. Physical activity is a great stress reducer. Go for that walk.

2) Social intimacy: Being around people you care about and that care about you, conversations and candor are major stress reducers. Most work situations have a competitive and hierarchical element the prevent true social intimacy, so friends, family, romance - these are the second greatest way to recover from stress, and replace cortisol with serotonin and dopamine. Feeling stressed out and want to hide out in your room or office? That is a mal-adaptive response: you are much better spending time with your friends watching a game, playing cards or just talking. Make that phone call.

1) Physical intimacy: including all forms of touch. I didn't see this one coming, but according to research this is the number one way to recover from stress. Replace cortisol with oxytocin, "the love hormone" through simple touches (I suspect pets might also play a role), handholding, cuddling, hugs and of course, private time with the one you love: this is the straightest path to recovery from too much stress. Horrible day at work? Think that coming home and immediately firing up the laptop to put out fires is the best way to handle it? Wrong. Counter-intuitively you are better off taking a break and spending a quiet romantic evening with your significant other. Time to light the candles.

Back to Dr. Ari's point about our inability to recover being the culprit for current stress levels? Consider the lifestyles of today vs. 100 years ago vis a vis these 3 mechanisms. 3) Exercise: 100 years ago we walked everywhere, most jobs had an element of manual labor and we were constantly active. Today the average office worker is completely sedentary nearly the entire day sitting a a desk with a computer screen. 2) and 1) Social and physical intimacy: 100 years ago more often than not we lived in multi-generational homes, and our work (farming, craftsmanship etc.) was more often a family affair. Homes were small, children slept 3 to a bed, and constant touch and interaction was the norm, not the exception. Consider today: for a single professional, most of the day, and night, are spent isolated and alone, and most social interaction - even dating - has become virtual in nature. Recovery is the key to resilience, yet many of us have lost touch with our most adaptive recovery mechanisms.

3. RAISE/REFRAME: Once you have regained balance and implemented stress recovery mechanisms back into your life, it is time for the real resiliency step: to intentionally take on MORE stress - in an episodic fashion - in order to recover even stronger. Raising stress is surprisingly easy: take on any new challenge that you can grow from. Go back to school for an advanced degree, switch jobs, vie for a promotion, take on a stretch assignment, have another child - options to take on growth oriented stress are virtually unlimited. But here's the real magic: all of those things can feel overwhelming, but perhaps the greatest resiliency tool is what my friend Dr. Daniel Friedland calls "reappraisal" or "reframing." We can learn to reframe stressful challenges to make them into a game or an experiment, where the outcomes, uncertain though they may be, do not directly link to our self image or self confidence. Mindfulness practice is a particularly helpful tool for reframing. Consider, for a moment, the Greek myth of Sisyphus: the king damned by the gods for all eternity to roll an immense rock up a hill only to have it roll right back down again. Sounds horrendous... but with a little reframing:

"Sisyphus learns to bowl"

Sisyphus' challenge was not all that different than bowling or the highlander games when you think about it. When we are able to reframe stressful challenges as a game or experiment we can begin to appreciate the process as much as the end result, reducing cataclysmic stress in the process. Sisyphus could have started to challenge himself, "how quickly can I get to the top? How heavy a rock can I move? How many times can I do it in one day? How strong can I get?" "Who is the strongest strongman on the planet?"

Perhaps the greatest story of reframing and resiliency comes from Victor Frankyl, author of "Man's Search for Meaning." A Holocaust survivor, Frankyl lost his mother, brother and wife to the Nazi concentration camps and experienced stress and privation well beyond what most of us will ever experience. But he was able to reframe his experience by choosing to view the suffering as an opportunity to serve others AND still find meaning.

"I understood how a man who has nothing left in this world still may know bliss, be it only for a brief moment, in the contemplation of his beloved."

Here is a man who has lost everything. On the brink of starvation, freezing, tortured, his mother, brother, wife dead, his life's work left behind and in ashes and he is able to find bliss. It certainly makes the risk of getting fired or missing a deadline seem paltry. I will end with Frankyl's most famous quote, one that sums up the ultimate reward of resiliency: freedom.